Mike Smith may be a world-famous artist, but his studio, crowded with different projects, thank-you notes, golf balls and a Specialized mountain bike suggest a man with a plethora of passions.And that’s pretty much how he’s lived his life. In fact, Smith never planned on becoming an artist. He considers himself lucky to have been in the right place at the right time on any number of occasions.

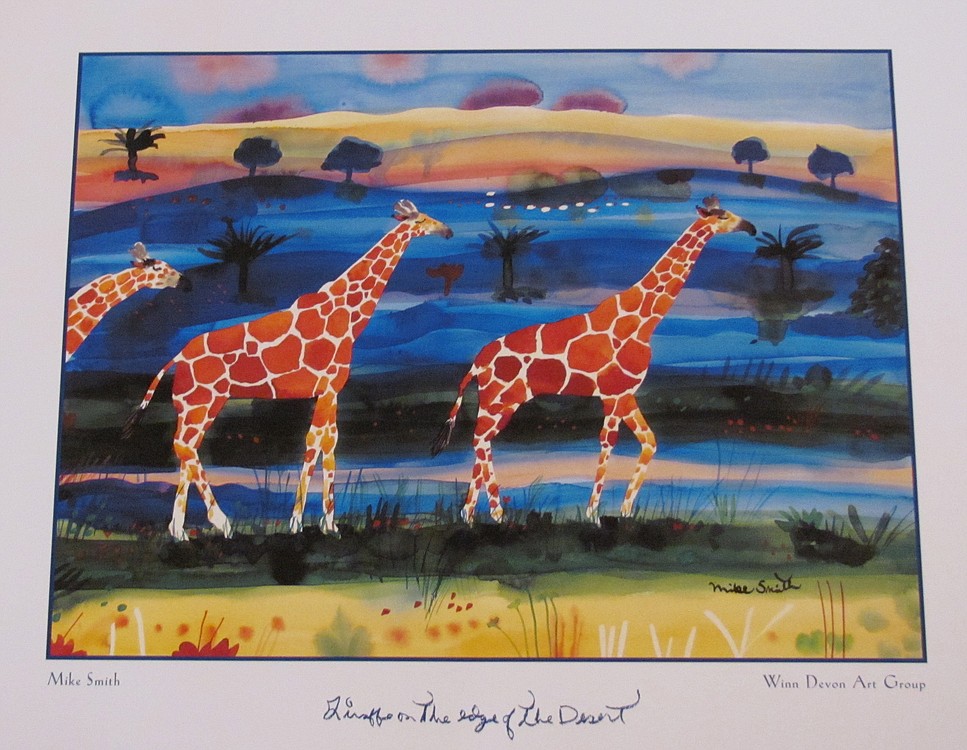

For example, during an art show in Hawaii, a representative of the Winn-Devon Art Group happened to see a pastel horse Smith had painted. He asked Smith if he’d be interested in turning it into a poster. That was back in the late 1980s. The poster has been displayed in waiting rooms at children’s hospitals around the world, with millions sold.

Usually, professional artists describe their work as a calling, something they always envisioned themselves doing. However, Smith didn’t envision painting for a career.

“When I was in school, I was a good artist, to the point of winning state shows,” he said. “But honestly, I could have cared less. I was too busy playing baseball. I was planning to be a baseball coach and a high school teacher.”

After graduating from Hudson’s Bay High School in 1960, Smith went to Clark College, then joined the Army. After his tour of duty was complete, he used the G.I. Bill to attend the University of Portland, where he earned a degree in English literature.